Finding Life – Anthea Buys

“Memory was supposed to fill the time, but it made time a hole to be filled. Each second was two hundred yards, to be walked, crawled. You couldn’t see the next hour, it was so far in the distance. Tomorrow was over the horizon, and would take an entire day to reach.” —Jonathan Safran Foer, Everything is Illuminated

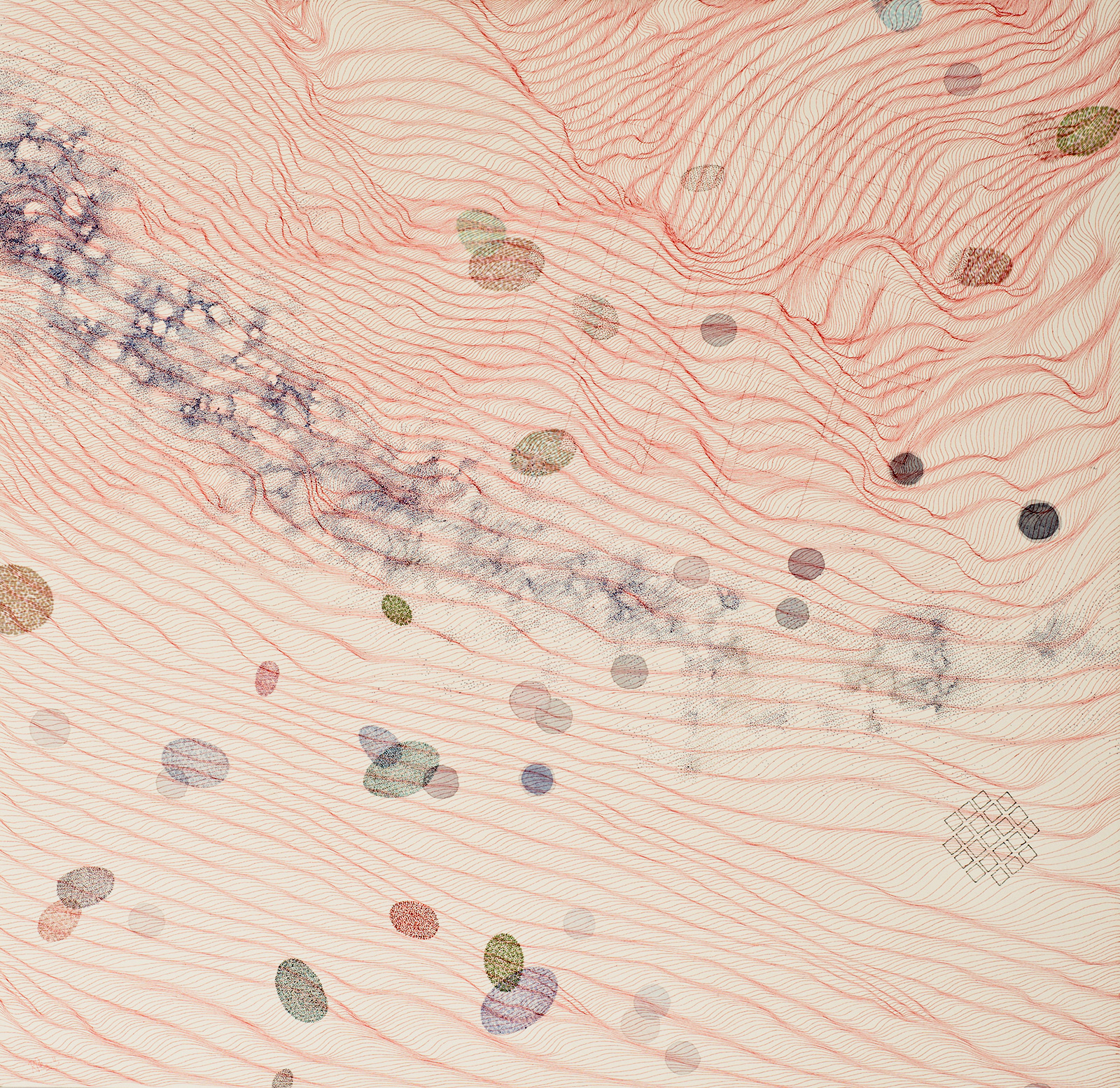

In an edgeless, undulating mass – it could be a bacterial culture, or slice of flesh – hundreds of forms float. Some look at first glance like ellipses filled with a granular gel; perhaps they are cellular things under the vigil of a laboratory microscope. They could be malicious or benign, doing work or destroying, somewhere deep inside my body. But if I imagine myself to be looking at one of these forms from very far away, rather than very close up, it could be a galaxy, clinging together with the help of giant forces across light-years of nothing and dust. Other marks buried in the striated background suggest plots of land, mechanical objects, fissures, plant matter, planets, lines of sight. Throughout Manifold i-xiii, a new series of drawings by Richard Penn, there is the paradoxical suggestion of being at once very close to, and very far from, the indefinable forms that populate the works. One becomes lost in pictorial scale.

In the same way, with the appropriate technology, the eye is able to equalise the enormous and the atomic. Lenses and artificial retinas of the sort used in space telescopes bring objects that are truly millions of light-years apart onto a single page, and molecules that are massed and indistinguishable from one another, perhaps even invisible by the billion, are scattered by the magnifying power of a microscope.

In Penn’s drawings in the exhibition Horizon, these ambiguous forms and their ground are minutely hand- drawn. They bear witness to the passage of a great many hours – hours belonging to a life, irretrievable hours. But, at the same time, they look humanly impossible, as if they have occurred out of a strange collusion between technology and nature. These forms have also come from accomplishments in making the invisible visible, in extending our horizons of vision. We now see not only further in scale, but further in space and, therefore, in time as well.

Penn’s interest in the ambiguity of scale began in his first solo exhibition Origin, held at the Substation gallery at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2009. In this show, which was dominated by two large video installations, he established an analogy between the grain of digital imaging, analogue magnetic “static” and hand-made marks. A series of short videos of the artist’s father, blurred and obscured by intervening transparent objects, pared familiar gestures and postures down to digital marks, pixels and dots. The implication was that a way of sniffing, for instance, passed from father to son, is no more than trained matter, a highly sophisticated system of cells and space. Alongside this work was a video animation in which digital interference, analogue television static and a blizzard of animated, hand-drawn dots were projected in a single channel onto the floor of the gallery. Penn cited a remarkable fact at the time: that the analogue static of a television out of tune occurs because of residual radiation from the “Big Bang”, the cataclysmic induction of the universe.

Origin was portentously titled. It has been the conceptual seedbed of all Penn’s subsequent work, which, if one were to abbreviate it, is about the coincidence of personal history and the scientific, “objective” history of a godless world. Godlessness, although never foregrounded in Penn’s work, is central to this motif. With the idea of god, or several gods, there is a closing off of things. The universe starts with a divine thought and eventually ends, the edge of the page delimits the picture. With god, there is no place for the protean dance of a work like Medium I, with its translucent watercolour dots and sickles clustering and spilling out of the bounds of the paper. With god, there is no use for telescopes; we would know we are not alone.

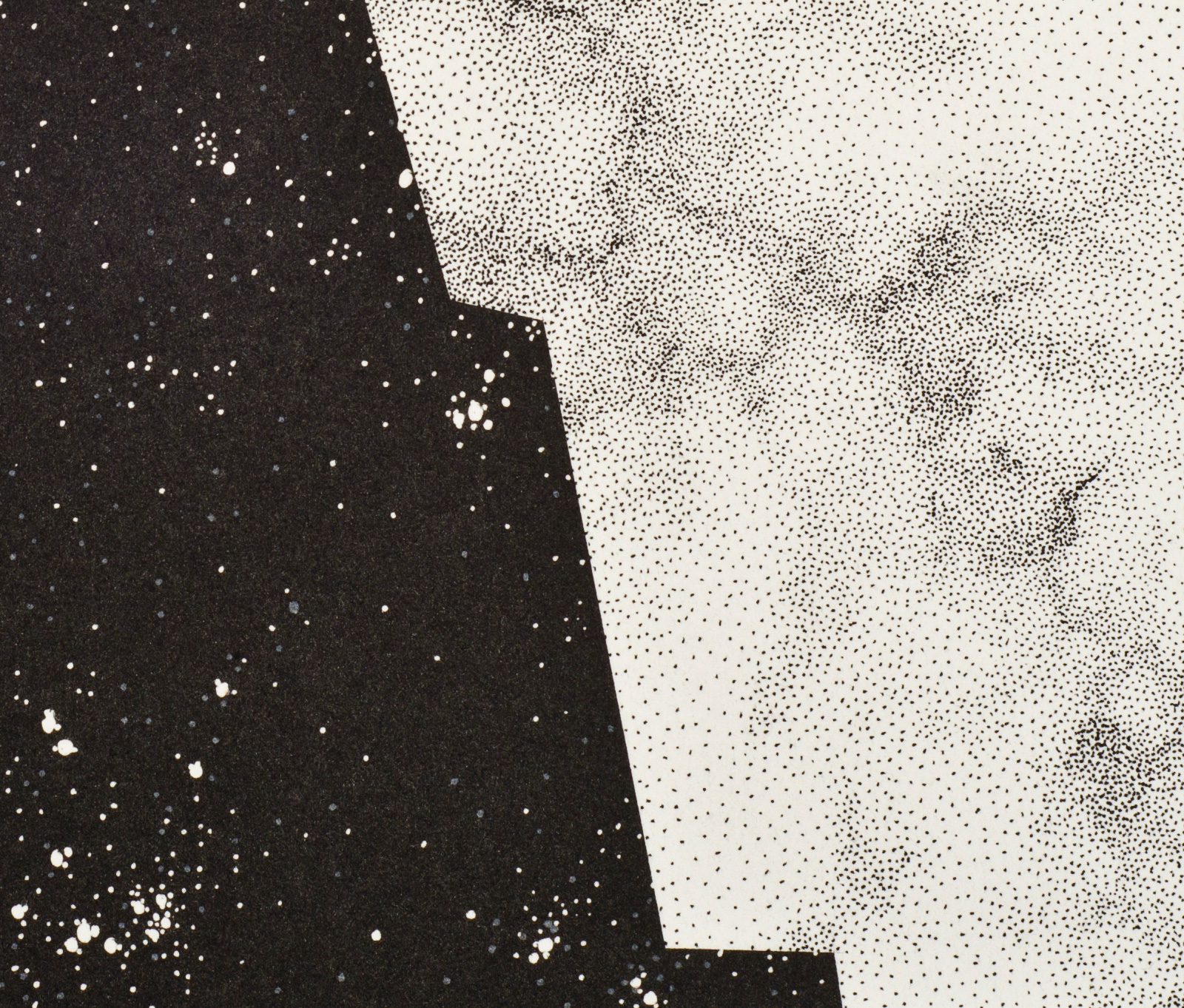

Two of the most vigilant telescopes to wander the heavens, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Kepler telescope, feature formally on Horizon, as shapes that frame views of different kinds of visual masses.The telescopes substitute god in framing and revealing a nameless manifold. But there is one crucial difference between the two agents, god and the telescope, and this is that the latter in Penn’s work leaves nameless that which it frames. We don’t know what we are looking at, and still we are looking very hard. In Penn’s own words, “As soon as you give something a name, it loses its meaning”.

The views inside Penn’s telescope shapes suggest the spectacular images of space that scientists have sold to the layperson as fact, but they also intimate, as I have mentioned earlier, microscopic organic processes. Like the Origin video portraits of Penn’s father, these new pictorial fields suggest a kind of internal portrait, an attempt to push the horizon of visualising life. Indeed, the possibility of seeing life, finding “evidence” of it, preoccupies space exploration. One of the most troublingly unresolved debates in astrophysics, known as Fermi’s Paradox, testifies to the difficulty of finding evidence of life in a universe so large that the odds of finding life there should be good. Scientists are torn between believing in the banality of life in a universe full of solar planets much like earth or the staggering uniqueness of something like life on earth having happened at all. Either option is likely to induce in the good atheist a kind of wholesome despair for those things which seem to be so much more than matter animated by chance. A loved one’s shrug may be one of these things, another, the sheer ability to make loved ones out of other lumps of matter.Horizon invites us to reconsider the criteria for evidence of life. We rely on our eyes to tell us our place in a universe the scale of which we must ultimately mediate, in whichever direction, with machines and prosthetic instruments. Things which look whole dissipate the more intimately we study them. Even the bodily material in which we have our being can be reduced to spacing and time.With a new palette, an entrée into watercolour and, with these, a new looseness, Penn embraces this dissipation. He makes a place for us in the present to look forward and backwards, close and far, and to find in this scattering a connection to the universe.

- HORIZON

- Gallery AOP, Johannesburg

- 25 February – 7 March 2012